The Bounded Text

The Bounded Text

“...text and textiles possess an overriding, perhaps unique, ability to communicate simultaneously on a multiplicity of levels. Stitch is rich.” – Sara Impey, Text in Textile Art (2013)

Context

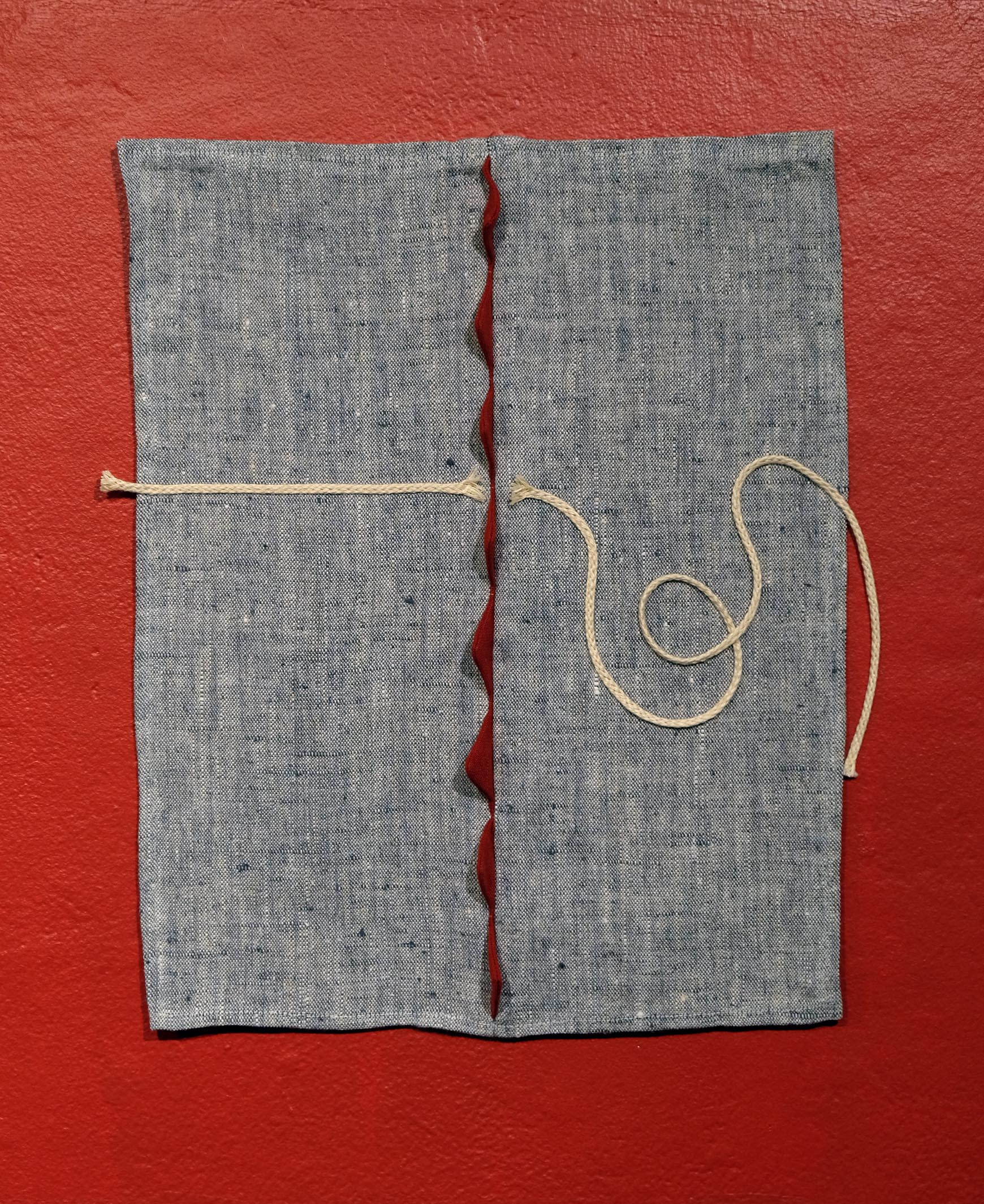

Textiles are supple materials made from a composition of natural or artificial fibres formed by weaving, knitting, crocheting, knotting, felting, spreading, bonding, or braiding. They are most commonly associated with objects of utilitarian purpose like clothing, furnishings, carpeting, towels, blankets, tents, and more. The artists in this exhibition, however, have chosen fiber as an aesthetic and conceptual medium over applied function.

Artist and author, Sara Impey has traced the ways in which visual artists have deployed text on textiles since before the eleventh-century Bayeux Tapestry – a 230’ long cloth embroidered with images accompanied by Latin script depicting historical events leading up to the Norman conquest of England. During the Renaissance, bookmakers would protect the pages of their illuminated manuscripts by binding them with elaborate, hand embroidered covers. Stitched lettering was a popular motif in decorative, domestic needlepoint samplers in the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries. Trade-union demonstrators famously created fabric banners emblazoned with slogans during early twentieth century strike marches. Some 1960s Conceptual artists included text in their artwork both in lieu of imagery, and as imagery in order to explore the relationship between idea, language, and meaning. As Impey points out that in literate society, reading is so instinctive “the brain interprets the simplest strokes and outlines as letters or numbers...If you can read, you do read.” (6)

The nouns ‘text’, and ‘textile’ are derived from the Medieval Latin word ‘texere’ meaning, “to weave”. Although we commonly associate text with the verbal realm and textiles with the realm of the physical, text is material. Just as textiles are made with fibers and yarns, phrases are composed of letters and words. And when manifested in fiber, text becomes physiological, or tangibly sensual. By the same token, fiber itself is a text ripe with aesthetic properties, cultural connotations, denotative meanings, and narrative chronicles.

Intertext

The title of this exhibition is borrowed from Julia Kristeva’s 1969 essay of the same name in which the Bulgarian-French philosopher, literary critic, psychoanalyst, and novelist outlines her concept of the ‘ideologeme’ – the intertextual function that materializes meaning within any text (Desire in Language, 36). Like written language (letters, words), all visual texts (lines, colors, images) harbor pre-existing discourses, histories, and permutations that are not always obvious at first read or glance.

In other words, authors and artists do not conjure texts from nothingness. Nor are artworks really unique, isolated objects of pure creativity. Rather, everything we write or make or even say, are compiled from pre-existing texts. Our job, as readers and viewers, is to recognize the intertextuality in the spaces between the words and images and threads we consume and use. To consider the various meanings of the component parts of the text – cultural, political, personal – even when they may remain hidden, or as they lie just beneath the surface of our collective unconscious. We must “read between the seams”, so to speak, and connect those lines to on-going social processes.

The artworks of The Bounded Text compel us to do just that. They combine words and phrases with the tangible materiality of textile to produce interpretations that are both literal and representative, direct and polysemous, visual and verbal. In their own, individual ways, these artworks are all informed by the structure and ordering of words...and threads. They reveal the fundamental connection between verse and fiber that is generally taken for granted and, in doing so, expose something about process and construction. Particularly the construction of language itself.